Introduction

During the course of studying video game engineering i frequently worked on projects that involved creating 2-D games or prototyping concepts for 2-D games. Since this is a very common type of project to work on, starting over from scratch every time seemed unnecessary, since these type of games share a decent amount of core functionality. If a generic framework that takes care of these core functions could be created, it would serve as a re-usable template that can be imported into new projects as a base for development. This would enable faster prototyping and development of games, allowing the developer to focus on the game logic unique to that game using a familiar framework and patterns. In this paper I describe the framework i developed called “GridGame” to meet this challenge and develop 2 prototype games as proof of concept.

Main Question

In order to solve to problem described in the introduction, the main question involves solving the following problem: Develop a generic framework that is able to serve as the core for a wide variety of games.

The framework must meet the following criteria:

- Take care of much of the boilerplate code for the game, allowing the developer to focus on game logic specific to the project.

- Provide the means for easy visual debugging of the data and state.

- Be able to pause and step through processing steps to help debugging.

- Be Generic and usable by a wide variety of games as possible.

- Replay and rewind functionality can be easily added.

- Library must be standalone and not require 3rd party libraries or rendering engines.

The following constraints apply to games that use the framework:

- Must be a game that uses a 2-D grid to represent its data

- Data model has to be deterministic: no floating point values or physics in the model. (physics and floats can still be used to visualize the data model)

Theoretical Research

While researching the subject of game architecture in general I came across a presentation by Yossarian King and Richard Harrison, of Blackbird Interactive, hosted at Unite 2016. Even though the presentation was mainly focused on designing architecture for multi-player games(King, 2016), I felt that the data-driven systems and game synchronization techniques could also apply to single-player games. In developing the grid game framework I seek to employ some of the high-level concepts mentioned by Blackbird interactive team, such as the separation of simulation and presentation logic and running deterministic simulations.

Model-View-Controller Architecture

The model-view-controller(MVC) is a widely known and implemented standard design pattern which separates an application into these 3 components. The decoupling of these components facilitates parallel development and allows for the reuse of code(Msdn.microsoft.com, 2017).

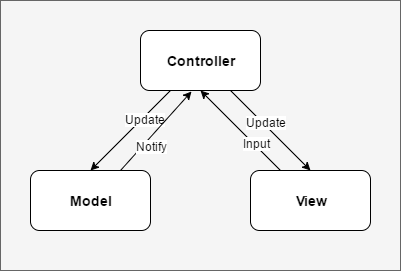

Figure 1. An example of the MVC components and communication between them

The model represents the data of the application and is completely removed from the view, or how the data will be presented. The controller is responsible for accepting inputs and updating the model and view accordingly. The view serves as the UI layer of the application and handles the presentation of the model and provides interactivity.

Presentation-Abstraction-Control Architecture

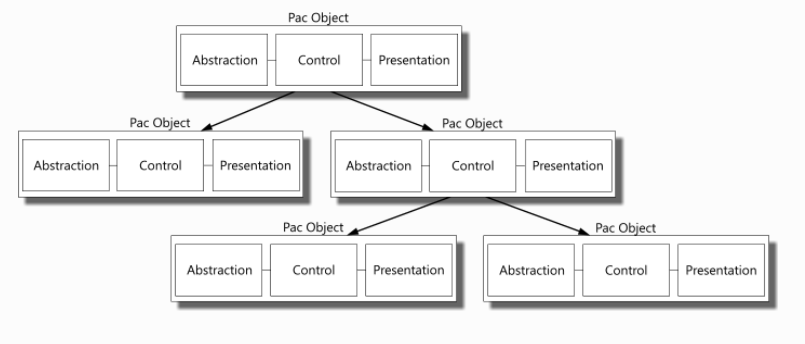

The Presentation-Abstract-Control(PAC) pattern aims to divide an application into a hierarchy of sub-system, where each component in the hierarchy is a PAC component providing a consistent framework for building user-interfaces at different levels of abstraction(Greer, 2017).

Figure 2. A diagram showing several PAC modules ordered in a hierarchy. Reprinted from Lost Techies, by D Greer, 2007, retrieved from https://lostechies.com/derekgreer/2007/08/25/interactive-application-architecture/

The control component is similar to the control component in the MVC architecture in that it processes events and user interactions. It also updates the data model and updates the presentation and in addition, sends update notifications to its parent in the hierarchy.

The abstraction component contains the data, similar to the Model in MVC however unlike the model, the abstraction may contain only part of the data model and does not communicate with the control or presentation.

Presentation is responsible for rendering the UI and plays the same role as the View component in MVC.

The command pattern

The command pattern is a data driven pattern that wraps a request as an object and passes the object to an invoker object which is responsible for executing the request(Tutorials Point, 2017).

To use the pattern a command base class is defined, from which different kinds of command classes inherit. These command objects define the different kinds of inputs the use can give in the program as described by Robert Nystrom in Game Programming Patterns (Nystrom, 2014). In GridGame, when a controller is declared it requires a generic type parameter defining what type of input the controller will be able to execute. In a simple game where only one kind of input can be sent by the user, there is no need to declare multiple sub-types of inputs, but the input must still be encapsulated in a data object for it to be stored in the input history by the controller. This was a design requirement added on my part in order to help make replay/rewind type functionality easier to implement, which was one of the design goals of the framework.

Because of its useful and generalized properties, and since in my opinion there is no need for a hierarchy of nested controllers, MVC was chosen as the base pattern for the grid game framework and the implementation will be discussed in further detail in sections below.

Model – The board

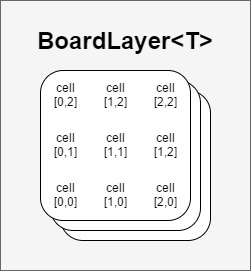

The data model in the grid game framework is a straight-forward structure consisting of an array of board layers, each containing a 2-D array of cells, which represents the playing field or board grid. Board layers are generically typed and a game can define an arbitrary amount of layers in the model.

Figure 3. Showing the board data model consisting of several grid layers of generic type.

A typical implementation would be to define a top-level board layer that represents the visual layer of the game(e.g. chess pieces and checkerboard in a chess game), and several “hidden” computational layers beneath. Using board layers as computational layers is advantages in terms of encapsulation as well as visual debugging, an example of this will be shown below in the match-3 game example. Using multiple layers is completely optional however, and the most simple implementation could using a single layer containing all the state data of the game.

Controller – Finite State Machine

A finite-state machine(FSM) is a model of computation based on a hypothetical machine made of one or more states. Only a single state can be active at the same time, so the machine must transition from one state to another in order to perform different actions(Bevilacqua, 2013). This pattern is often used to control the execution flow of a program.

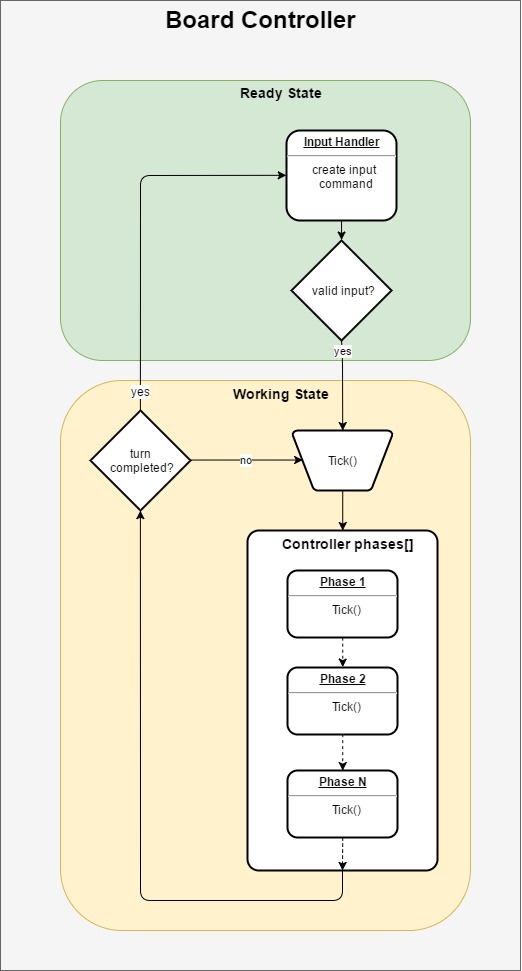

Figure 4. An illustration of the controller state machine and its processing flow during a turn.

In GridGame the controller consists of a FSM with two states: ReadyForInput and Working. While in the ready state the controller waits to receive a valid input, once a valid input arrives, the controller switches to the working state and starts to process the controller phases.

A game can define any number of controller phases, which are registered in an array in the controller. When in the working state the controller processes the phases in sequence and once completed finishes the turn and switches back to the ready state for the next turn.

The controller has a public Tick() function, which in turn calls Tick() on the phase currently being processed. This allows the developer to control the execution of the controller phases, e.g. manually call tick while debugging, or automatically keep ticking until the turn is completed in normal gameplay.

View

The framework is designed to strongly decouple the rendering of the game from the game logic. Therefore the framework provides a model and controller structure, which the developer can attach a rendering system of their choice. In the two prototype games discussed below the Unity engine is used as the rendering engine for the games.

Match-3 prototype

In order to test and demonstrate the framework two prototype games were developed. The first of these is a standard match-3 puzzle game, where the player swaps 2 adjacent gems in order to match patterns and score points to reach a target score within a predefined number of moves. The model, view and controller components are described in sections below as well as gameplay video.

Match-3 Model

The data model consists of a 7×7 board containing several board layers. The Fields layer is primary, and contains the data that will be displayed by the view, in this case the fields and gems. The matches layer marks cells on the board that form part of a match group with an id number. The candidates layer does the same thing, accept this time marking “match candidates”(groups that are one swap away from a match). The trickler layer is used by the trickle phase to calculate how gems should fall due to gravity after match explosions.

Figure 5. The data model of the match-3 game consisting of 4 layers.

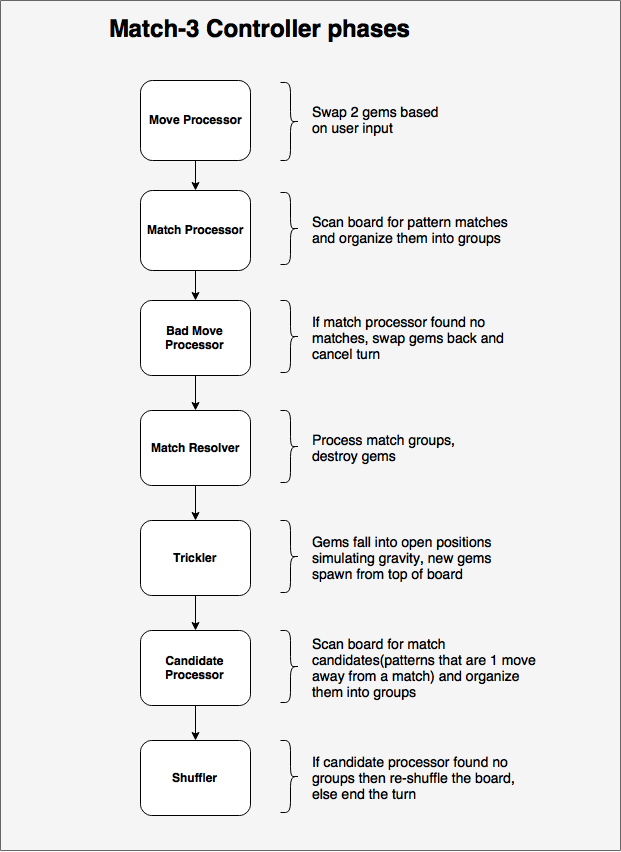

Match-3 Controller

The controller consists of several phases which are processed in sequence every turn. A phase modifies one or several board layers by calling its Tick() function until the phase marks itself as completed, and the controller moves to the next phase in the sequence.

Figure 6. An illustration show the 7 individual processing phases of the controller in the match-3 prototype.

Match-3 View

Presentation of the match-3 game is handled by unity. Controller phases that modify the view make calls to an animation controller which handles executing the different animations that keeps the board view synchronized with the model. Below is a gameplay video showing normal gameplay, as well as visual debugging turned on.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zgrb0CTj3bA

2048 – Prototype

The second game built to test the GridGame framework is a clone of the math puzzle game 2048. The game was originally developed by Italian developer Gabriele Cirulli in 2014, and was itself a clone of an earlier game called 1024 by Veewo Studios.

The game is played on a 4×4 grid with numbered tiles. Every turn the player inputs the direction the tiles should slide that turn(up/down/left/right). Tiles slide as far as possible in the given direction and if two tiles with the same value collide, a new tile with the combined value of the tiles spawns in their place and adds to the player’s score. After every turn a new tile with value two or four spawns in a random empty position on the board(Cirulli, 2014). The game ends when the board has no more empty slots and there are no equal value tiles adjacent to each other at the end of a turn.

The board model consists of two layers, the primary layer contains the integer values of the tiles. The second “gravity” layer keeps track of the gravity state of each tile on the board and is used to process the sliding and colliding of tiles on the board.

The Controller has two phases. A gravity processor handles the sliding and matching of tiles based on the input direction. Then a Spawn processor creates a new tile in a random position and also checks the game over conditions before ending the turn.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pj-iyi0bC-E

Visual Debugging

One of the requirements set out in the main question is for the framework to make it easy to implement visual debugging in games. In order to achieve this, an optional LayerDebugger object can be attached to board layers during instantiation of the board. A Layer debugger takes a board layer of a generic type, as well as an anonymous “converter” function that evaluates the object type of that board layer and outputs a string.

Figure 7. Code sample of the layer debugger class and how it converts a generic type to a string output.

When a layer is debugged by calling the GetLayerState() method, the converter evaluates each cell on the board and assigns it a debug string. The output of all cells is collected in a 2-d array and returned. From there it is up the the renderer to display the debug information.

In the unity prototypes, the debug text of cells are rendered on a canvas overlaying the board(optionally turned off as below), and cells are colored based on the output text. Below the match-3 visual debugger shows the matchmaking and trickle layers being processed.

Figure 8. Animated gif showing visual debugging steps in the match-3 prototype.

Replays

Another requirement for the framework is to make it easy to implement replays of levels. Since some games may not wish to implement replay functionality at all while others might want to have advanced rewind or replay capabilities, the framework does not implement replays built-in, however tries to make implementing replays as simple as possible.

As an example case, the match-3 prototype has a replay system that makes it possible to save the replay of a level that was played, and be able to re-watch the replay later. A typical use case of this would be for play-testers to be able to save a replay of a session where a bug or error occurred, and send it to the developers to be able to replay the level and see what causes the issue.

When a user plays a level, the board controller records each input the player makes during a game and stores it in an array. When a level is completed a replay.json is created which contains the level data, the random seed used(this is important to ensure the same random events occur again when replaying the level), and the history of inputs.

Figure 9. Diagram indicating the flow of inputs from the user or replay file as well as the saving of a replay as json.

When playing a level in replay mode, instead of waiting for inputs from the user, the board controller grabs the next user input object stored in the replay array and uses that as the input for the next turn. Since the game is deterministic and the same random seed is used, the replay is guaranteed to play out exactly as the user did initially. The replay only saves the initial state of the board and a list of small input objects, therefore the replay json file remains small in size, even for long games.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The main goal of the GridGame framework is to take care of much of the boilerplate code, and provide a consistent foundation when developing 2-d grid based games. While the framework is not suitable for every kind of game, it aims to be generic enough to be widely applicable.

Games that are suitable for the framework include:

- Tower defense

- Math puzzlers

- RTS

- Arcade puzzle

- Board games(chess/go/checkers/etc)

At this stage the frameworks handles regular square 2-d grids, but lacks support for hexagonal grids. Since many 2-d games are designed to be played on hexagonal grids, this feature would make the framework more widely applicable and should therefore be developed further.

Overall the framework satisfies the conditions of satisfaction stated in the main question and significantly reduces boilerplate code and development time of prototypes.

Full source code is available at: https://github.com/zoidbergZA/GridGameFramework

References

- King, Y. (2017). Unite 2016 – Building Multiplayer Games with Unity. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://youtu.be/-_0TtPY5LCc [Accessed 6 Apr. 2017].

- Msdn.microsoft.com. (2017). ASP.NET MVC Overview. [online] Available at: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dd381412(v=vs.108).aspx [Accessed 6 May 2017].

- Nystrom, R. (2014). Game Programming Patterns. [online] Gameprogrammingpatterns.com. Available at: http://gameprogrammingpatterns.com/ [Accessed 13 Jun. 2017].

- http://www.tutorialspoint.com. (2017). Design Patterns Command Pattern. [online] Available at: https://www.tutorialspoint.com/design_pattern/command_pattern.htm [Accessed 18 Apr. 2017].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2017). Presentation–abstraction–control. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presentation%E2%80%93abstraction%E2%80%93control [Accessed 19 May 2017].

- Bevilacqua, F. (2013). Finite-State Machines: Theory and Implementation. [online] Game Development Envato Tuts+. Available at: https://gamedevelopment.tutsplus.com/tutorials/finite-state-machines-theory-and-implementation–gamedev-11867 [Accessed 26 Jun. 2017].

- Greer, D. (2007). Interactive Application Architecture Patterns | Aspiring Craftsman. [online] Lostechies.com. Available at: https://lostechies.com/derekgreer/2007/08/25/interactive-application-architecture/ [Accessed 15 Jun. 2017].

- Cirulli, G. (2014). 2048 (video game). [online] En.wikipedia.org. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2048_(video_game) [Accessed 12 Jun. 2017].